RAWing with Paul Langan answering the five questions of doom

- Tell me how you got started writing, in particular writing for teens. Why did you focus on writing books with an urban setting featuring youth of color?

I wrote my first short story in 6th grade. It was almost Halloween, and my reading teacher challenged our class to write a scary story. The winning story would be selected by the class and receive a $5 prize. I was a new kid in the school, and I wrote my story about the thing that scared me the most—a classmate who spent much of his time shoving me in the hallways and threatening me on the playground. In my story, he met a glorious end at the hands of a horde of bully-hungry zombies. He got attention, which he liked, but I got that $5 prize and discovered a new tool to deal with difficulties in my world: writing.

Many moons later, I worked for Townsend Press as a coordinator for a summer reading program for Philadelphia 8th graders. My goal was to get kids reading. To do that, we created a reading contest. Kids would select a book straight off teacher recommendation lists and bestseller charts. They’d read it and call our toll-free reading hotline where I’d confirm they finished the book. Prizes, including cash, were awarded based on the number of pages each student read.

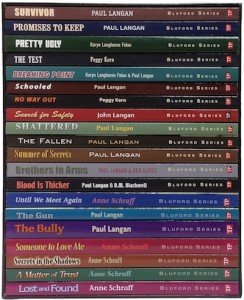

We had fun that summer, but I discovered our students, mostly African American teens, seemed uninterested in the titles teachers recommended. Instead, they gravitated toward novels set in cities, featuring protagonists that looked like them (a rarity in the YA world in the late 1990’s). In retrospect, we should not have been surprised that they preferred books that spoke to their experiences. But at the time, this idea was revolutionary. The kids schooled us. The lesson was simple: if we want young adults to pay attention to books, we need to give them books that pay attention to them. That idea sparked the Bluford Series.

2. Bluford is popular for lot s of reasons, but in particular often with kids who can’t or won’t read other books. In your opinion, what are the elements of a successful book for reluctant teen readers?

Confession. I’ve never liked the term reluctant reader. I’ve seen many with this label become avid readers—once they get the right book. Why don’t they have it? One culprit is reluctant publishers. For too long, mainstream publishers refused to acknowledge or embrace young readers of color. This is well documented by greater minds than me, and it is changing (finally). But traditional publishing still seems reluctant to address the issue of access. Listing a hardback book for $19.99 online or in a suburban bookstore is evidence of the problem. In crowded neighborhoods in Philly, Chicago, or Detroit, for example, bookstores are rare. Municipal libraries are underfunded. School libraries are being shuttered. Money for books and eBooks is limited. As a result, many teens don’t get to experience exciting YA books. Is it fair to call them reluctant readers? I don’t think so.

And sometimes we actually teach them to be reluctant. Kids without access to books tend to have reading experiences confined to what’s taught in school. Often these books are far removed from students’ interests, and they come with baggage: quizzes, writing assignments, worksheets, book reports, etc. These tasks make reading a punishable activity. For strong readers, this work can be dull. For struggling readers (more often boys), this work can leave them discouraged or frustrated. Years of this in school can destroy enthusiasm for reading. It may even lead students to conclude books have nothing to offer—or to give up on reading altogether.

The Bluford Series was crafted to change this. Bluford stories attempt to reintroduce reading to teens who have, for whatever reason, abandoned books. Each novel is set in bustling inner-city Bluford High School, a place one reader called “Hogwarts in the ’hood.” Each story begins with a situation that has emotional hooks that resonate for young adults: the desire to connect and be accepted, the longing for love and respect, the pain of loss or rejection, the feeling of being misunderstood by family or friends, the sting of betrayal and rivalry, the difficulty of being young and confused and uncertain, the magical intensity of growing up. These sparks burn bright in young adults.

In addition, the books are short (less than 200 pages), giving teens who may think they dislike reading a chance to finish a book. Many write to me saying Bluford novels are the first they’ve ever voluntarily completed. Some describe feeling as if something was wrong with them because, for the first time in their lives, they stayed up all night reading. A few have even said they thought they were ill because their hearts raced and they forgot about dinner while reading!

To produce this reaction, Bluford novels move quickly and include lots of action and suspense, starting on page one if possible. They also, I hope, pack an emotional punch, leaving readers with something to think and, perhaps, talk about. This combination allows the books to compete with smart phones, social networking, and video games for teens’ attention—not an easy task. It might also convince them to give books a second chance. That was the intent from day one.

3. Tell me a little bit about the deal with Scholastic coming out with the Bluford books with different covers, and in one case, a different title. What, if any other changes, did you need to make to make the Scholasticable? (is that a word?)

I like the word! I may have to borrow it. Yes, Scholastic approached us years ago and expressed interest in distributing the Bluford Series. Townsend Press, my employer, is a small educational publisher. We lack the reach, expertise, and distribution muscle of Scholastic and were delighted they felt our novels were potentially Scholasticable.

We agreed to terms in which both Townsend and Scholastic could distribute the books. Their marketing team felt that photograph-based covers made more business sense. They also requested that we change the title of one of our books—The Gun—for fear some bookstore chains may refuse to carry it. To appease them, I renamed that book Payback, an alternate title I had all along.

4. Okay, the big question: so I reluctantly read a blog review of Outburst in my The Alternative series. This book tells the story of an African American teenage girl coming out of detention and going into a foster home. The review began with “Jones, who is white …” and I wished I would have stopped reading there. Have you faced this being a white male writing stories for and about kids of color? Most everybody seems to be onboard with we need diverse books, but not if those books are not written by people of color. What are our thoughts on this issue?

Ah, yes. The Big Question—worthy of more than a few paragraphs!

I’ve been around the block for a while now. Early on, I visited schools where readers—teens and adults—didn’t know I was white until my pasty face appeared in the front office. I heard readers exclaim, “Oh my God, he’s white,” more than a few times. I have also heard my books described as “ghetto novels,” a racially charged term with positive and negative meanings. Still others have suggested I’ve “neglected” or even discriminated against white readers by not featuring white protagonists. Others are angry that I’ve written such books, arguing that I have no right to do so.

Race is our cultural third rail, and it is woven right into our national DNA, whether we want to admit it or not. We are all impacted, and we all play a part. If you choose to avoid the issue or look away, you’re playing a part too, a passive one.

Most writers, myself included, are not passive. If we were, we wouldn’t choose this path. When you decide to write, you make a commitment to be true to what you are creating. That means doing your homework and research, mining your experience, and delving through your own creative process to tell the Truth. Your readers deserve all you can give (and sometimes more). So do your characters. If you get it wrong, both will abandon you.

For Bluford, I chose to set events in a city school, similar to the schools students in our summer program attended. For believability and realism, I made this fictional high school mirror the population in those schools. As a result, few students at Bluford High are white. That’s reality! Unlike most YA books, especially in 2001 when Bluford appeared, nonwhite characters are not relegated to the sidelines. They are not minor players or token characters. Instead, they are the centerpiece, the heroes and foils, parents and children, principals and janitors, bullies and targets, veterans and neighbors, police officers and thugs in every story. Sometimes they are many of these things at once. Like all of us, they are complex and multi-layered with their own histories, secrets, and mysteries. They are also, I hope, full of contradictions, flaws, talents, fears, hopes, beauty and ugliness—traits that are authentically human. Real.

I get letters all the time. My favorites are those that say, “I know you’re white, but it’s okay because you totally get it.” I treasure these because as a writer and fellow human being, I want to get it. It is the prime directive.

Of course, there are some things as a white man I will never fully understand. While I have many experiences which inform my work, my white skin makes my American experience different than that of my characters and many of my readers. This is complex territory too big to fully address here, but as a white writer, I must account for it, examine what it means, own up to it, and always remember it. This is our cultural backdrop, but it is not an excuse to avoid or ignore readers of color. That approach has been standard practice for far too long, and we see where it leads. Let’s change it. I think all writers should join in this effort. All readers matter.

Regardless of background or history, writers share a single challenge: to breathe art and Truth into their work. Readers get to decide whether we are successful. It’s that simple. To paraphrase the Bard, the story is the thing.

Does the story hold up? Does the writer get it? Does the art resonate? If yes, there’s nothing more to say. I aim for yes.

5. What are you working out now? In addition to writing Bluford books, what else do you do for Townsend Press?

We’re a small independent educational publisher, but we have a big reach. We produce materials—novels, leveled books for emerging readers, reading/writing texts for schools and colleges—that engage students and help teachers teach. The Bluford Series is just one part of that. We also sponsor various programs to assist schools with limited budgets. As an editor at Townsend Press, I have many responsibilities outside the Bluford Series. Lately I’ve spent much time working to digitize our offerings. But I am happy to say I’ll be returning to the Bluford Series full-time next year, and a new Bluford book, in the works for some time now, will be out this fall. We’ll post details about it soon on Bluford’s Facebook page, https://www.facebook.com/Bluford.Series

Permalink

thanks for the fantastic interview!

Permalink

Wow, in another life I must have been a blood relative, possibly twin, to Paul Langan because our current life missions do in fact mirror each other. I’m a reading teacher that’s been using his books since 2008… no other publishers outside of Townsend Press have so fully met the needs of my students from 5th to 8th grade. I love this interview and feel so grateful to have read it. I’ll be sharing it whenever I’m promoting Townsend Press to my colleagues in education.